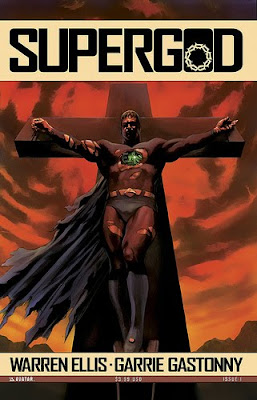

Supergod, to be written by Warren Ellis and published by Avatar Press in November, promises a wealth of content for those of us who like to indulge in the discussion of superhero theology. From Ellis himself on the upcoming miniseries:

Supergod, to be written by Warren Ellis and published by Avatar Press in November, promises a wealth of content for those of us who like to indulge in the discussion of superhero theology. From Ellis himself on the upcoming miniseries:Supergod is the story of what an actual superhuman arms race might be like. It’s a simple thing to imagine. Humans have been fashioning their own gods with their own hands since the dawn of our time on Earth. We can’t help ourselves. Fertility figures brazen idols, vast chalk etchings, carvings, myths and legends, science fiction writers generating science fiction religions from whole cloth. It’s not such a great leapt to conceive of the builders of nuclear weapons and particle accelerators turning their attention to the oldest of human pursuits.... And, perhaps, there’s still that little scratchy voice in the middle of the night: I don’t want to be alone. I want there to be something bigger, something that moves in mysterious ways and wants only the best for us. And I will forgive it, the disgusting state of this world, and all the things in it that want to crush and kill me, and have faith that something incredible and invisible and unknowable will make things better. And so (in Supergod), just to make sure, I will build it and keep it by me. I will pretend it’s a weapon, a defensive capability, a computing object or a construction machine — but really it is a Messiah.So it seems that Ellis plans to take the metaphysical element of our fascination with superheroism and turn it around to comment on our tendency to seek out gods in places where we probably shouldn't. It sounds like a brilliant idea. As much as I like to write about the true spirituality hidden within every hero story, there's no denying how easily real people misplace their hopes and trust in things that have no inherent eternal significance. With mythological underpinnings being brought to the surface in many of today's comics, perhaps it's a good idea for someone like Ellis to tell us to step back and reconsider.

As far as I can tell, there are two major slants on this notion that Supergod could take.

It could be written as a condemnation of idolatry. The chief sin of the Christian faith and also claimed to be so by the other Abrahamic religions, idolatry as an attitude goes beyond the simple worship of statues and carvings. It occurs whenever one takes anything in God's creation, whether tangible or not, and places on it a higher importance than God himself. Through this lens, the admiration of super-powered "messiahs" in Supergod can be said to be foolish because these beings are not God.

More likely than not, however, Supergod will probably turn out to be a reprimand of mankind's search for god in anything, period. Ellis's work in the past, such as Planetary and The Authority, has generally betrayed an atheistic worldview. Ellis's description above of the concept of god as a product of human want also appears to promote this ideology. If this is indeed the perspective from which Supergod was written, then the foolishness of messianism by the characters therein will be likened to the pursuits of any who hold to theistic convictions. Christians, Muslims, and Hindus alike will be skewered for the way in which they chase after imaginary gods of their own creation!

Such a tone, no matter how cleverly executed (and with Ellis at the helm, it no doubt will be very clever), will inevitably result in a weaker story in this reader's eyes.